I don’t know whether I’ve mentioned, before, the miserable circumstances under which I spend my days, Monday to Friday.

It’s a sort of software sweatshop — we’re all lined up at benches, no privacy at all, and most horribly, no quiet. In my case the situation is even worse, because two Russian guys sit across the bench from me.

Now as everybody knows, Russians are great motor-mouths to start with, and these two are especially voluble and combative. They argue and scold each other nonstop in Russian — or almost nonstop; they occasionally take a break to argue with, and scold, somebody else, on the phone.

I know, or rather once knew, a little Russian, and so I pick up maybe one word in ten, and of course they drop a little English vocab into their conversation — nivitz gevizt mozhe buy superclass. VITZ?!

So it’s pretty distracting.

My never-sufficiently-to-be-praised wife bought me a pair of noise-cancelling headphones, and when it gets really bad, I plug them into my phone and try to find something to listen to that won’t distract me too much from what I’m doing but will drown out the Russians.

Debates in the British parliament are a godsend; nothing very demanding is being said but everybody seems to be having a good time. It’s like a sitcom. William Hague is actually quite likable, in a horrific kind of way, and Ed Miliband is such a pathetic damp squib that he brings out my inner sadist — the kind of person who would laugh at a blind guy slipping on a banana peel.

I also listened, recently, to some archived interviews, on NPR, with John Updike, a writer who was never in my pantheon — though I’ve read his stuff with more than slight pleasure. On the radio he was indescribably delightful; a bit arch, a bit fey, but very perceptive and always seemed to find the right word. He gave the impression of being a shy guy who had managed to assemble a suitably self-protective public persona, but without misrepresenting himself. I greatly envied his rather whispery, level, unemphatic voice. I too am a shy guy but my public persona has the plummy, orotund voice of Senator Claghorne.

Updike was a riot on the subject of that unspeakable monster Michiko Kakutani. I was laughing so hard the Russians stopped talking (mirabile dictu) and shot me a puzzled glance.

Ordinarily I can’t listen to music. Too demanding. I can’t think of anything but the music and I start to write the strangest, most disconnected Python code. But on a particularly bad day recently, Youtube offered up a complete Art of the Fugue, played on the organ. Out of curiosity, more than anything else, I fired it up, and from the first five notes of that apparently simple but Protean and ultimately spooky theme, I was, as always, putty in the hands of that sui-generis old sorcerer, Herr Kapellmeister und Kantor Johann Sebastian Bach, blest be his name unto ages of ages.

To paraphrase another spooky old gent, Dante Alighieri, very little Python code got written for the next half hour. Unfortunately — or perhaps fortunately, if you take into account that the rent must be paid — the available data rate, in my corporate ziggurat, wasn’t enough to keep up with the old boy’s counterpoint. Maddening gaps and hiccups at last frustrated me so much that I tore the headphones off, with a muffled oath.

It’s been a while since I heard anybody play the Art of the Fugue. It’s not a crowd-pleaser. But a great deal of nonsense has been spread about this… this what? Not a ‘piece’. Not a collection of pieces. A secret garden? A labyrinth that somehow grows larger, that expands into new dimensions, as the visitor works his way toward the heart of it?

People say it’s music for the eye, or the head; bloodless, cerebral, ethereal. Very ‘great’, of course, whatever that means, but at the same time, somehow, a bit eccentric and dead-end.

Whether anybody will ever take up where old JSB left off, in measure 239 of contrapunctus XIX, is anybody’s guess, of course. So maybe it is a dead end, in some sense — or better, the living end.

But bloodless it is not. Every measure, as I hear it, is charged with passionate intensity — with feeling so deep it can’t waste itself in gesture and rhetoric, those usually charming and amiable attributes of the music we so oddly call ‘Baroque’. The KdF just speaks itself, in the plainest of terms; it follows its own thought to the deepest heart of its matter, and invites us — without persuasion, much less the hard sell, without any airs or graces — to come along if we like.

I came home from the job and dug out my old Dover edition and played, very slowly and haltingly, through the first two contrapuncti. To see the notes on the page, to feel all that godlike largesse unfolding itself under my own thick, unskilled fingers… if I try to describe it, I’ll just embarrass us both.

I found that I wanted to shed all my Early Music habits; to indulge in rubato like a highwayman; to play some notes loud and others soft; to put it over, in fact. A thing I don’t usually do much of, beyond a very modest level.

This seems wrong. But I don’t want to be robotic about it, either.

Because I now have my mission. Before I die I want to learn all the contrapuncti. They’re nearly all pretty manageable on manuals and pedal, though there are a few spots that want a terza mano.

I wonder what my captive Episcopalians will make of this, when I get to bestride the bench. Perhaps some will think the contrapuncti dull, though clearly most respectable.

Others, better informed, will think I’m being self-indulgent, and of course they’ll be right.

Perhaps the best I can hope for is that somebody will have the experience I had, fleeing from the world of my quarrelsome Russian friends, and re-discovering the strangeness and wonder of a country I thought I knew.

Bravo, Michael!

Yeah, this is another fantastic entry! Your job sounds like a fucking nightmare.

The corporate workplace — at least my corner of it, the Niflheim inhabited by the IT Nibelungs — has become a startlingly more horrible place since I first descended into it, back in ’76. In my own experience, the bad turn really came to be felt sometime in the 90s.

One of these days I’ll write about ‘Agile development methodology’ — of course these people never say ‘method’, it’s always ‘methodology’. Taylorism applied to programming.

Comrade Smith, your reference to the Agile bullshit is endearing. Of course, I think it’s a thousand times better than the other bullshit that the Americans have exported to the rest of the techweenie world: PMI Methodology. Yours truly refused to succumb to this crap and I never got my PMI certification but my last job in America forced me to become a Scrum Master! I must admit, I am envious of you for still being a programmer. I myself moved on to this project management bullshit sometime in my 40’s after years of being a Fortran and Oracle programmer because I didn’t think anyone would hire a middle aged bird as a programmer. Now of course I regret it.

Your experience with your Russian coworkers mirrors mine with my Romanian coworkers (no shortage of them in Montreal). It was the exact same office setup as yours and the Romanian Row was on the other side of the trough. In addition to the regular loud arguments back and forth in Romanian peppered with a few French words here and there, they used the company line to call Romania and yip yap for hours (sticking it to the man was their only virtue!). Alas, I finally walked after 6 weeks and am now looking for work as, you guessed it, a Scrum Master!

BTW, I can’t wait for your piece on Agile bullshit. Now pull out your deck of cards and give us the estimate and it better not be the infinity card.

Wow, I just looked up ‘agile development methodology’ and it looks horrific! Taylorism is applied to everything nowadays. If you can do ANYTHING more efficiently, i.e. faster and cheaper, then why would you consider doing it any other way? A lot of people I know begin their descriptions of nearly everything with a report of how long it took and how much it cost, with those obviously being the determining factors in enjoying something like a meal or a trip to the beach.

A noble goal. I wish I could play the organ.

If you want to deal with people in the work place who drive you crazy, and increase your work productivity to boot, go to the gun section of a 24 hour Walmart, buy eighty of these bad boys so you don’t run out, and insert them as directed. They’re effective at the home front as well.

What ever happened to Al Schumann?

I’ve been wondering the same.

Herr Smith,

Do you know what portrait you have used as an illustration? Is it the one mentioned in Glen Wilson’s pleasant notes to his 2010 (MP3 only) recording of the Goldberg’s, which notes I copy from Naxos Music Library? (Please bleep this if there are copyright concerns.)

From NML:

Bach contributed masterpieces to most of the variation forms current in his day: the Passacaglia, Canonic Variations, and chorale partitas for organ, the Chaconne for solo violin, the choral passacaglia of the Crucifixus of the B minor Mass; even the Art of Fugue is a huge variation ricercar. Yet of variations for harpsichord or clavichord he wrote only two sets—few enough, considering the great popularity of variations and Bach’s striking devotion to the instruments. His first biographer, Johann Nikolaus Forkel, touches on the reason for this when he speaks of “variations, which, on account of the constant sameness of the fundamental harmony, he had hitherto considered as an ungrateful task.”

The main motor of Bach’s music is the development of a limited number of melodic figures through highly dynamic harmonies. In baroque variations, where the number of bars remains identical, the situation is reversed: the static harmony compels a search for ever-changing melodic formulas, and, to give each movement the motivic unity baroque esthetics required, each variation is usually based on a sole motif. This system, says Forkel, Bach found too confining.

There is an early trial effort, the beautiful Aria variata alla maniera italiana, BWV 989. Then, after an unfinished fragment in the first Clavierbüchlein for his second wife Anna Magdalena (ca. 1722), he turned his back on harpsichord variations until twenty years later, when he took them up again with a vengeance.

The famous story of how he came to do so is in Forkel. The Russian ambassador to the Dresden court, Count Kayserling, had in his entourage a brilliant young harpsichordist, Johann Gottlieb Goldberg, whom Bach taught in nearby Leipzig. “The count once said to Bach that he should like to have some clavier pieces for his Goldberg, which should be of such a soft and somewhat lively character that he might be a little cheered up by them in his sleepless nights…He was never weary of hearing them, and for a long time, when the sleepless nights came, he used to say: ‘Dear Goldberg, do play me one of my variations.’ Bach was, perhaps, never so well rewarded for any work as this: the Count made him a present of a golden goblet, filled with a hundred Louis d’ors…It must be observed that, in the engraved copies of these variations, there are some important errata, which the author has carefully corrected in his copy.”

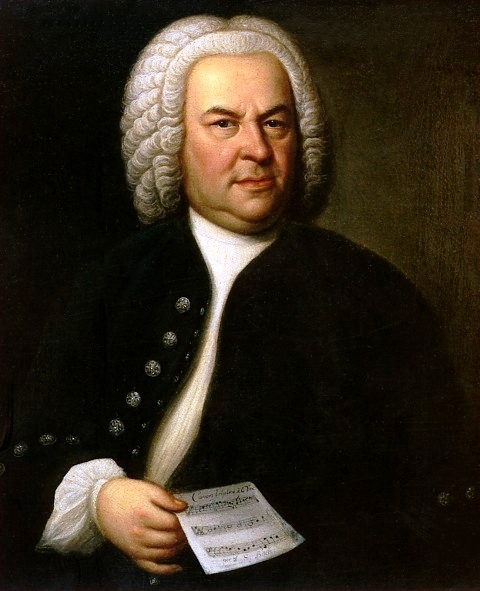

The last sentence was sensationally confirmed in 1975, when Bach’s copy of the original edition came to light. Besides corrections and many added ornaments, it contained fourteen puzzle-canons on the first eight bass-notes of the Aria, the discovery of which more than doubled the number of his known canons. One of them appears in his late Leipzig portrait, where he peers out at us with a humorously challenging expression, inviting us to try our luck at solving the riddle of a canon triplex a 6 Voc. He even had it separately printed, like a calling card. His pride was justified, for no other music ever written so resembles the harmonia mundi—the theme, its mid-section, and its falling fourth plus inversion, in simultaneous triple canon with their inversions, like mirrors reflecting mirrors into infinity.

The variations themselves are a brilliant fusion of Italianate virtuosity—Bach certainly had seen sonatas by his contemporary Domenico Scarlatti—and the prevailing French influences in Leipzig. Gottsched had turned the city into “a little Paris”; Voltaire, travelling in 1750 to Potsdam and Frederick, wrote home: “I find myself in France. German is spoken here only by soldiers and mule-drivers”. Looking across the Pleisse from his Komponierstube, Bach saw a French formal garden. The Aria itself, a Polonaise, a nod to Kayserling’s Polish homeland, is a heavily French-ornamented conversation galante straight out of a novel by Madame de Lafayette.

The layout of the Goldberg Variations suggests, in its numerical rigour and strict symmetries, a baroque palace. The thirty variations are flanked by the Aria and its da capo, like a long façade with pavilions at each end. The central axis is marked by Variation 16, a French (!) overture. In order increase the specific gravity of the whole by injecting some solid German counterpoint into his fabric, Bach made all the variations which are multiples of three canonic, with two upper voices in strict imitation and a free bass. Variation 3 is a canon at the unison, Variation 6 a canon at the second, and so on, the interval of imitation increasing by steps until, at Variation 27 (3x3x3), a canon at the ninth (3×3), the accompanying bass drops away. The canon in Variation 15 marks the halfway point by inverting the imitating voice. The aria and each variation is a microcosm of the whole, having 32 measures in two sections of sixteen bars. The remaining variations are a catalogue of dance movements, a fughetta, trio sonatas, and gorgeous cantilenas. One of these, the sombre-hued Variation 25, Landowska called “the black pearl of the set”.

This plan is certainly masterly. But one could write a set of variations on the same plan and still have it come out as rubbish. Or one can play the Goldberg Variations, plan and all, and still play them badly. The plan gets too much attention; it is as a menu to a great meal, or a map to journey—a mere starting-point. The music holds riches such feeble analysis can barely hint at. In fact, probably no composition has suffered so much at the hands of its interpreters. The “soft and somewhat lively character” of Kayserling’s variations tends to get lost in febrile technical show, especially in the cross-hand variations, which on an historical harpsichord can only be played with the lightest of registrations. A teacher of mine compared them to “Régence filigree”. At the time, I was too young to have any inkling of what he was talking about.

A Canadian pianist and his admirers turned the work into a thing of such hyper-tense, modernist rigidity that, hearing it, the poor Count’s sleep would have been eternal; and many present-day harpsichordists have substituted the gait of a drunken sailor for any sense of tempo. But the Goldberg Variations will survive all abuses, until such intelligent life as exists on our much-abused planet is finally extinguished.

Glen Wilson

I’m pretty sure the folks I’m working for are hiring. I can’t promise it’s better but at least they haven’t figured out how a proper corporation ought to be run (in spite of their best efforts).

I got moderated!

So I try again with a change from a long quote to a link.

Is this portrait of the beloved Bach the one mentioned in the CD notes by Glen Wilson?

http://www.naxos.com/mainsite/blurbs_reviews.asp?item_code=9.70009&catNum=9.70009&filetype=About%20this%20Recording&language=English#

A performance of the music shown in the portrait at approximately 12:10 here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8nIqjXh1xgE

not exactly corp., but…

http://www.criterion.com/films/27877-a-report-on-the-party-and-guests

Bravo Superclass Smith,

There remain patrons – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j1r2GF7ovL0

Hey, if anyone is out there, I think a comment monster is eating the comments to the previous posts. Hopefully this gets to you before it has an opportunity to eat this one as well!