From one of my mailing lists:

Marxism is the legitimate successor to the best humanity produced in the nineteenth century, as represented by German philosophy, English political economy and French socialism.

I don’t exactly disagree with the writer of this, but there’s something blockheaded about it, which disturbs me.

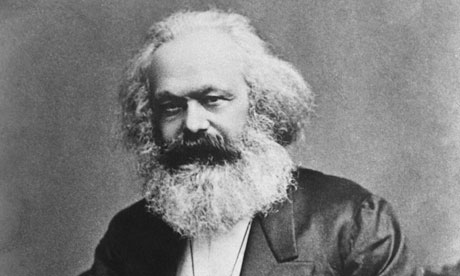

Old Karl is one of three thinkers born in the 19th century whom I deeply admire; the other two are Darwin and Freud. And for Karl, at least, I also feel an intense personal fondness. I just like the guy. I think that tossing back a few beers with Karl would have been fun, and I’m not so sure about that with respect to the other two.

‘Best of the nineteenth century’ seems right, though it was, overall, a hell of a bad period; and therefore, perhaps, the phrase, though no doubt well intended, is in fact fainter praise than the Moor deserves.

What struck my eye was the three sources my correspondent listed: German philosophy, English political economy, and French socialism. Talk about unpromising materials! And yet my correspondent is right, up to a point: these were the books Karl had on his shelf.

All these confluent streams are shallow and polluted, and yet old Karl, swimming in such insalubrious waters, came up with notions that can still set us thinking, and even acting.

What bothers me, perhaps, about my correspondent’s phrasing is an implicit suggestion that Karl winnowed out the bad and kept the good; that his activity was, so to say, redactive.

This couldn’t be more wrong. All the bad stuff about Karl is the nineteenth-century stuff; the belief in ‘progress’, for example. That comes from ‘English political economy’. And all the stuff that’s completely unreadable and incomprehensible comes from German ‘philosophy’. And all the dated polemics — which are, admittedly, fun to read — come from French socialism.

So where did the good stuff come from? I have my own thoughts on the subject, but I’d like to hear yours.

But what to you consider the good stuff? The best stuff? Isn’t that preliminary to ‘where it came from’?

Well, I’m embarassed to have to admit that I don’t know nearly enough about Marx to have an opinion on which is the good stuff or the bad stuff.

As far as knocking down a few brews with Marx — yeah, I can totally see that. I couldn’t possibly see it with Freud, though; he somehow strikes me as more of an absinthe man.

I dunno, maybe the good stuff — for me — is the notions that fermented in my own head as I read the old boy. It’s too big a topic for a blog, perhaps.

Please, you must indulge us!

Y’know, I feel a little shy about it. I’ve read Marx more shallowly and less extensively than I would like, and there are plenty of people out there who are real experts — though I must say that some of them don’t seem to have derived much illumination from their expertise.

It’s a slow Sunday and if the comrades are short of materials to read, I highly recommend the following “insider’s” account of the chronology of events during the Montreal’s student movement last winter and spring. The author is obviously an anarchist who took part in the battles. It’s a very long piece and if you get bored, fast forward to important dates such as April 20th and May 4th: the Battle of Victo. If you don’t want to read the whole thing, just watch the video compilations sprinkled throughout the piece, which would give you a better sense of the intensity of la lutte:

http://crimethinc.com/texts/recentfeatures/montreal1.php

By the time Marx wrote his thesis (on Epicurean thought), he had a million ideas swirling around in his head. My guess is that these began to coalesce into his mature thought when he began to become aware of social struggles. When feudal relationships started to unravel in Germany, Marx was a newspaper editor, As peasants lost their traditional land rights, Marx took up their cause and saw that he would have to study economics. Later in England, he made wonderful use of the Factory Inspectors’ Blue Books, which brought to light the dreadful conditions of the working class. His partnership with Engels was important too. Maybe as he saw the world around him, the various currents of thought in his brain and his tremendous learning started to come together to produce what I think are the only works of true genius in what are now called the social sciences. Perhaps, a kind of clash between Romanticism and Enlightenment marks his works too.

As E.P. Thompson noted at a time when the “crisis of Marxism” was becoming too obvious for any but the true believers to paper over:

There may be plenty of Geschichtenscheissenschlopff around to supply opium for Marxisant intellectuals, but the rest of us need better models grounded on terra firma to extricate ourselves from the morass.

I’ve warmed to Karl myself. That fact I was taught to respect him during my “higher education” took some getting over. But–like anyone other great I respect–there are disciples who annoy the shit out of me. A Facebook comrade linked an article (I can’t now find) that, if taken literally, rejected any for of environmental activism on the grounds that a) it would effectively advance Malthus’ reactionary, “naturalist” agenda and b) technological progress–as Marx apparently “proved”–is boundless if we set ourselves to it. Which in practice would mean were it discovered a company had contaminated the town’s drinking water we shouldn’t do the only thing that has probed effective–if anything has–and break out the pitchforks; rather we’re to hold out until scientific progress yields a modification to the human genome that enables us to safely metabolize arsenic. Funny how it’s the worst qualities of outstanding people that are often the most enduring.

Perhaps the heartland of industrial development, and its class formation – less terra ignota – helped move him along — lots of terra firma [early corporate structure, 14 hr work days, child labor, everlong parliamentery debates about ‘what is capital’, all pushing for greater exploitation, absolute surplus to owners, etc etc]

But more likely his philosophic education and the methodology he developed [which is one reason to read what – he – wrote and not someone’s interpretation, particularly a Stalinist version – though [Rosdolsky [sp?] – certainly no Stalinist – seemed good.

To end this with what some might even enjoy – The Method of Political Economy [a fairly short section from Marx’s ‘Grundrisse’ –

http://marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1857/grundrisse/ch01.htm#3

And please recall the subtitle to Marx’s Das Kapital:

A Critique of Political Economy

Forgot to mention that, within today’s division of labor, he might be best understood as a sociologist and/or anthropologist, but I am far from being an expert ‘Marxologist’.