Apparently if you're an angel, you don't need to have your steering oar in the water, in order to steer. I could use some crew like that on my little boat.

A recent discussion here about Alex Cockburn -- who is of course a notorious and much-execrated "climate-change denier" -- has motivated me to try and organize my muddled thoughts on the subject (climate change, I mean, not Alex Cockburn).

I've helped build some computational models myself, and have opened and examined the innards of others. These experiences have taught me that models are tricky things.

They're highly dependent on the parametric assumptions that go into them, for one thing. Those assumptions usually seem reasonable, and when the modelers are honest, which they mostly are, the assumptions are nearly always at least as justifiable as the contrary assumptions would be, absent any real evidence either way. But still, you're out on a limb -- an apparently thick solid limb, maybe, but a limb nevertheless.

Then there are the dynamical components -- the rules that derive one quantity from another at each iteration of the computational process. Typically these are abstractions from observational data -- nice smooth mathematically concise functions that fit the noisy data you have pretty well, and are often further justified by physical models of the phenomena in question. You can usually make a good case for these, but here again, they represent a methodologically necessary simplification of the actual world, where many different forces interact, often in a chaotic and/or path-dependent way.

None of this is to say that the climate-change models are worthless or wrong. Personally, I think they're more likely to be right than wrong, at least to a first approximation.

But there's plenty of scope for skepticism. It's not a nutty stance to take the models with a grain of salt. People who reproach Cockburn for his skepticism usually end up citing the expertise and knowledge of the modellers, and asking what the hell qualifies Cockburn to talk about atmospheric physics. And to be sure, aliquando bonus dormitat Homerus -- Alex has been known to put the occasional foot wrong when he ventures onto the treacherous turf of, say, thermodynamics.

But the argument from authority is not only logically weak, it ought to be repugnant to anybody on the Left. (Liberals, of course, love and revere authority, but who cares about them?)

The authorities and the institutions that support them are highly susceptible to groupthink, enforced orthodoxy, agenda-driven ideation, and unexamined, even unconscious, assumptions. History is full of cases where the expert consensus was dead wrong.

The of course there's the awkward fact that the earth has seen many cycles of extreme temperature variation, which as far as I know, climate science has yet to convincingly explain. This rather substantial lacuna in our understanding of the phenomena in question doesn't tend to bolster the authority of the authorities.

* * * * *

Personally, I'd like anthropogenic global warming (AGW) to be true. Unlike Alex, who loves to ride around in old gas-guzzler American boat-cars, I'd like to plow under three-quarters of the pavement in North America, and scrap nine-tenths of the cars. When people express worries about global warming, it offers an opening for my always-ready anti-car, anti-house, anti-suburb Jeremiad. But these various anti's of mine don't arise from a concern about global warming. They have a quite different basis, and they've been among my articles of religion from long before anybody was worried about global warming.

Doesn't the same hold for many of us? AGW is, for us, a convenient truth, Al Gore notwithstanding. As Dr Johnson said, I know but two causes of belief: evidence and inclination. Few of us have really investigated the science; but for many -- myself among them -- the inclination to believe is very strong.

* * * * *

Let's think about the politics of the thing. Ask people why they get so mad at Alex for his denier-ism, and they'll tell you, It's so important! Something must be done!

But is it not perfectly plain that in fact nothing will be done? There's no movement to assist or impede, no progress for Deniers to hold back. All respectable opinion agrees that AGW is real and a serious problem, and yet it is clear that the elites are quite determined to let it happen, if it's going to happen.

Oh, it's a convenient way of getting nuclear power started up again, and creating modest but pleasant pools of public largesse for certain sectors of industry. Cap-and-trade is yet another wonderful opportunity for plunder by the Visigoths of Wall Street. But you won't be seeing a carbon tax -- the only policy lever yet discussed which has any chance of making a difference, as far as I can tell; you won't be seeing any noticeable disinvestment in road- and car-building, or corresponding increase in transit construction or operating subsidy; you won't be seeing any changes in zoning laws or any less encouragement for house-ownership and green-field sprawl development.

In fact the battle against global warming was over before it began, and global warming won. That being the case, what does it matter whether one admits or denies the phenomenon? Isn't the question... academic?

* * * * *

Yet people go purple in the face nowadays when you mention Alex Cockburn to them, and they sputter -- if they're not too enraged for articulate speech, at all -- "That Denier! May his name be blotted out!"

Whence this emotional investment in the topic? People don't get nearly as mad as this about ongoing things that are actually and unquestionably killing real people in large numbers every day. But AGW, though somewhat conjectural and certainly not an immediate problem, is a subject that even liberals -- maybe even, especially liberals -- get tremulously passionate about.

In a sense, it's a perfect liberal issue. It's not -- at least, not the way it's usually posed -- a class issue; it's not workers vs. bosses. To be sure, if it happens, the wretched of the earth will be made a lot more wretched, and the highly comfortable little less so, if any. And this fact is occasionally mentioned in polemics on the subject. But it isn't the reason why liberals are so keen on it, I think.

It's the sort of thing our institutions ought to be able to deal with, if they worked as advertised. Come, let us reason together, and then appoint a panel of experts to execute. Science has spoken, and now the apparatus of technological rationality must be put in gear.

But technological rationality is spinning its wheels on this matter; and Science is the voice of one crying in the wilderness. Why?

One liberal answer is, in effect, demonic possession. There are some powerful villains -- not, Lord knows, the elites in general -- who are too stupid or greedy or bloody-minded to acknowledge the problem. These Bad Unreasonable People are like some sort of infectious agents in the body politic, interfering with its proper functioning and blocking the efforts of Good Reasonable People like Al Gore. This sort of dualism between the enlightened and nice people, and the unenlightened and nasty people, is very dear to the liberal heart. (Needless to say, the Bad Unreasonable People are mostly Republicans, and if not for them, it's quite certain that the Good Reasonable Democrats would do the right thing.)

The other liberal answer is that people in general are just no damn good -- all those porcine dolts out there with their SUVs and jet-skis just won't be parted from their vulgar amusements and comforts. If only people in general were more... more... well, more like us. This picture, too, is never far from the merit-class mind.

The answer that can't be entertained is the structural one: the idea that our society, as presently constituted, is going to take us all right over the cliff because it can't do otherwise.

Nothing very political about this post.

Nothing very political about this post.

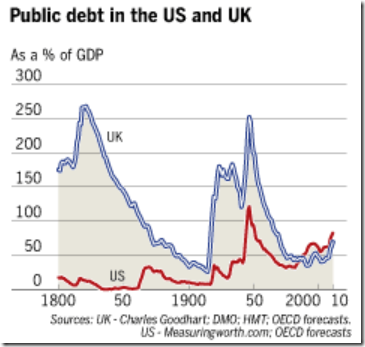

My man Simon Johnson, he of the

My man Simon Johnson, he of the

.gif)