I don’t know whether I’ve mentioned, before, the miserable circumstances under which I spend my days, Monday to Friday.

It’s a sort of software sweatshop — we’re all lined up at benches, no privacy at all, and most horribly, no quiet. In my case the situation is even worse, because two Russian guys sit across the bench from me.

Now as everybody knows, Russians are great motor-mouths to start with, and these two are especially voluble and combative. They argue and scold each other nonstop in Russian — or almost nonstop; they occasionally take a break to argue with, and scold, somebody else, on the phone.

I know, or rather once knew, a little Russian, and so I pick up maybe one word in ten, and of course they drop a little English vocab into their conversation — nivitz gevizt mozhe buy superclass. VITZ?!

So it’s pretty distracting.

My never-sufficiently-to-be-praised wife bought me a pair of noise-cancelling headphones, and when it gets really bad, I plug them into my phone and try to find something to listen to that won’t distract me too much from what I’m doing but will drown out the Russians.

Debates in the British parliament are a godsend; nothing very demanding is being said but everybody seems to be having a good time. It’s like a sitcom. William Hague is actually quite likable, in a horrific kind of way, and Ed Miliband is such a pathetic damp squib that he brings out my inner sadist — the kind of person who would laugh at a blind guy slipping on a banana peel.

I also listened, recently, to some archived interviews, on NPR, with John Updike, a writer who was never in my pantheon — though I’ve read his stuff with more than slight pleasure. On the radio he was indescribably delightful; a bit arch, a bit fey, but very perceptive and always seemed to find the right word. He gave the impression of being a shy guy who had managed to assemble a suitably self-protective public persona, but without misrepresenting himself. I greatly envied his rather whispery, level, unemphatic voice. I too am a shy guy but my public persona has the plummy, orotund voice of Senator Claghorne.

Updike was a riot on the subject of that unspeakable monster Michiko Kakutani. I was laughing so hard the Russians stopped talking (mirabile dictu) and shot me a puzzled glance.

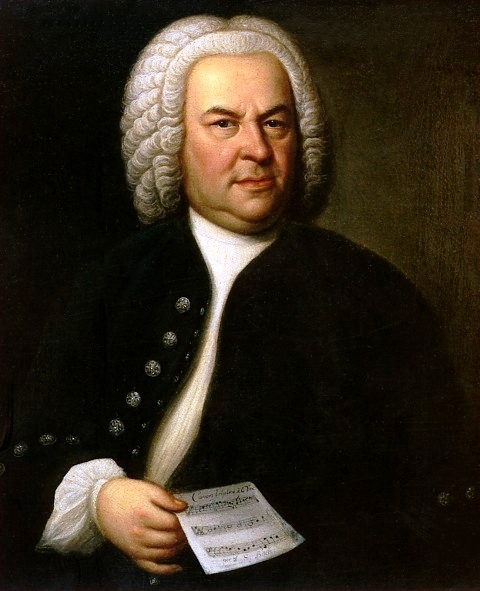

Ordinarily I can’t listen to music. Too demanding. I can’t think of anything but the music and I start to write the strangest, most disconnected Python code. But on a particularly bad day recently, Youtube offered up a complete Art of the Fugue, played on the organ. Out of curiosity, more than anything else, I fired it up, and from the first five notes of that apparently simple but Protean and ultimately spooky theme, I was, as always, putty in the hands of that sui-generis old sorcerer, Herr Kapellmeister und Kantor Johann Sebastian Bach, blest be his name unto ages of ages.

To paraphrase another spooky old gent, Dante Alighieri, very little Python code got written for the next half hour. Unfortunately — or perhaps fortunately, if you take into account that the rent must be paid — the available data rate, in my corporate ziggurat, wasn’t enough to keep up with the old boy’s counterpoint. Maddening gaps and hiccups at last frustrated me so much that I tore the headphones off, with a muffled oath.

It’s been a while since I heard anybody play the Art of the Fugue. It’s not a crowd-pleaser. But a great deal of nonsense has been spread about this… this what? Not a ‘piece’. Not a collection of pieces. A secret garden? A labyrinth that somehow grows larger, that expands into new dimensions, as the visitor works his way toward the heart of it?

People say it’s music for the eye, or the head; bloodless, cerebral, ethereal. Very ‘great’, of course, whatever that means, but at the same time, somehow, a bit eccentric and dead-end.

Whether anybody will ever take up where old JSB left off, in measure 239 of contrapunctus XIX, is anybody’s guess, of course. So maybe it is a dead end, in some sense — or better, the living end.

But bloodless it is not. Every measure, as I hear it, is charged with passionate intensity — with feeling so deep it can’t waste itself in gesture and rhetoric, those usually charming and amiable attributes of the music we so oddly call ‘Baroque’. The KdF just speaks itself, in the plainest of terms; it follows its own thought to the deepest heart of its matter, and invites us — without persuasion, much less the hard sell, without any airs or graces — to come along if we like.

I came home from the job and dug out my old Dover edition and played, very slowly and haltingly, through the first two contrapuncti. To see the notes on the page, to feel all that godlike largesse unfolding itself under my own thick, unskilled fingers… if I try to describe it, I’ll just embarrass us both.

I found that I wanted to shed all my Early Music habits; to indulge in rubato like a highwayman; to play some notes loud and others soft; to put it over, in fact. A thing I don’t usually do much of, beyond a very modest level.

This seems wrong. But I don’t want to be robotic about it, either.

Because I now have my mission. Before I die I want to learn all the contrapuncti. They’re nearly all pretty manageable on manuals and pedal, though there are a few spots that want a terza mano.

I wonder what my captive Episcopalians will make of this, when I get to bestride the bench. Perhaps some will think the contrapuncti dull, though clearly most respectable.

Others, better informed, will think I’m being self-indulgent, and of course they’ll be right.

Perhaps the best I can hope for is that somebody will have the experience I had, fleeing from the world of my quarrelsome Russian friends, and re-discovering the strangeness and wonder of a country I thought I knew.