More Albert Speer architecture envisioned for the Nineleven(tm) memorial. This particular exercise in brutalism will conceal a branch office of the New York medical examiner’s office, where various scraps of human corpses will be kept — frozen, I presume — pending “identification”.

There will be a ‘viewing room’ for the families, who, we are assured, will not be charged admission. The families apparently also have a viewing site of their own over the whole Nineleven theme park — a sort of skybox, I suppose.

The combination of ghoulishness, sentimentality, and grievance privilege exhibited here seems very, very American.

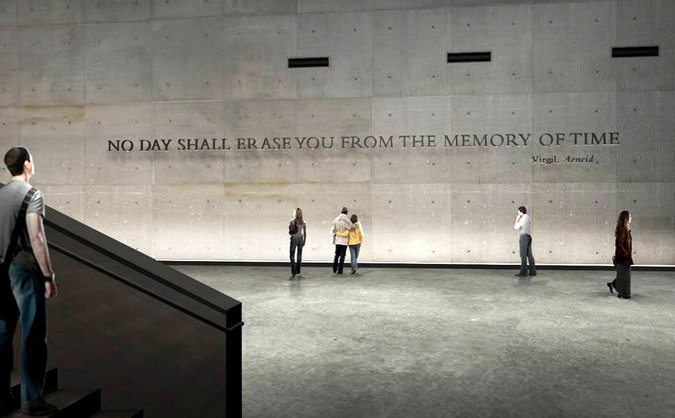

You can see in the picture above that there is to be an inscription on the wall, picked out in — what else? — letters of steel, salvaged from the skeletons of Nelson and David(*).

The inscription is a rather pedestrian translation from Aeneid IX. The poet is addressing the shades of Nisus and Euryalus, two terrorists from Aeneas’ band of settler-colonialist invaders, who embarked on an errand of nocturnal assassination against the native resistance movement led by Comrade Turnus. After slaughtering a number of natives in their sleep, Nisus and Euryalus got their well-deserved comeuppance.

Virgil, of course, knows how to put a good face on this sort of thing:

Fortunati ambo! Siquid mea carmina possunt,

nulla dies umquam memori vos eximet aevo,

dum domus Aeneae Capitoli immobile saxum

accolet imperiumque pater Romanus habebit.

Nicely Englished by my man Dryden:

O happy friends! for, if my verse can give

Immortal life, your fame shall ever live,

Fix’d as the Capitol’s foundation lies,

And spread, where’er the Roman eagle flies!

— though Dryden rather softens Virgil’s bluntness; the last two lines translate literally: “While the house of Aeneas occupies the immovable Capitoline rock and the great Roman father holds his empire.”

“Erase”, I must say, is a rather odd choice of words for ‘eximet’, which doesn’t mean anything quite so graphic; it’s just unemphatic ‘take away’. But ‘memori aevo’ is a lot better than the lame ‘memory of time’; it means something like ‘the remembering age’.

Unlike Nisus and Euryalus, the dead of Nineleven didn’t deserve their fate. Apart from that, there is a certain appropriateness, intended or not, in the choice of quote.

(Mutatis mutandis, as the Romans say.)

The gory tale of Nisus and Euryalus, in Virgil’s genuinely sublime and incomparable imperialist tract, takes its place among the uncompromisingly violent and unapologetically thuggish foundational narratives of Rome. Virgil wants it there; his exegi-monumentum poetic confidence tells him he can place it there; and he makes it stick. We remember Nisus and Euryalus because Virgil raised them a monument more lasting than bronze.

What the dullard plodders contriving Ninelevenland have in common with Virgil is the shared program of legitimating empire. Virgil does it by showing Nisus and Euryalus as bold impulsive gallant fellows — and ardent lovers as well. Irresistible, eh?

But the soul-engineers of Ninelevenland don’t really have this option as regards their Immortals (and probably couldn’t handle it if they did). What they have to fall back on is the rhetoric of American victimhood: poor us. So ill-used; so misunderstood.

Somehow I don’t think that a monument more lasting than bronze can be erected on this basis.

Update: Apparently the compromising context of the original has been pointed out to somebody in the theme park’s management cadre. The response? Drop the word ‘Aeneid’ from the attribution. Hey, if we do that, people will think it’s from the Georgics!

—————

(*) As the two boxy towers were unaffectionately known in some circles — the reference being to the two Rockefeller brothers who ran, respectively, the state of New York and the Chase Manhattan Bank.