Since I’m not on the boat at the moment, and haven’t had to drive anywhere lately, I haven’t had to listen to NPR. But occasionally I walk into the kitchen unexpectedly, to find one of my household furtively tuned in to Fresh Air or something. I never object, but even so, it’s like an old Radio Free Europe TV ad I remember from my youth: A ragged, frostbitten Eastern European family huddled around an ancient tube radio of vaguely Gothic design, a single, naked, flickering light bulb suspended from the ceiling casting Fritz-Langian shadows. Then a peremptory knock at the door, terror on every pale, high-cheekboned face, the dial rapidly twirled to WCOMMIE…

One of these early-morning raids on my part was rewarded the other day by hearing some ‘journalist’ or ‘analyst’ or ‘political scientist’ burbling on about Congressional ‘gridlock’ — a fine durable old cliche, that. She predictably bemoaned the fact that nobody was willing to ‘compromise’. So far, the usual NPR white noise.

But then she made my jaw drop.

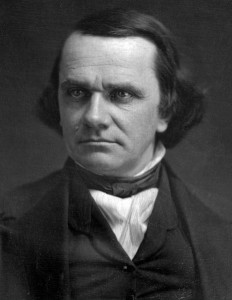

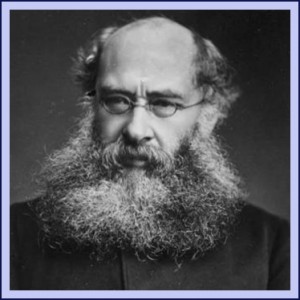

She mentioned –approvingly — the notorious Compromise of 1850, and held it up as an example of what the Administration and the Democrats ought to do. Instead of pushing for what you might call a comprehensive compromise, covering all the contended topics, break it up into half-a-dozen smaller bills and assemble slightly different coalitions to pass each.

I don’t recall whether she mentioned the Fugitive Slave Act, one of the crown jewels of the Compromise. If so, it was in parentheses. I was too stunned by her chipper sum-up: “It postponed the Civil War for ten years!”

Now among historians, of course, one finds many Lords of The Subjunctive, who will tell you very confidently what would-have-happened-if. And among this tribe there are those who say that if the war had come earlier the North would have lost. The extra ten years bought time for the North to industrialize, etc. A little like the Hitler-Stalin pact. And though the slavers got ‘popular sovereignty’ in the Utah and New Mexico territories, abrogating the earlier Missouri Compromise in their favor, the Subjunctivists will assure you that these territories would never have gone slaver.

What there’s no ‘if’ about is that the slavers got out of the Missouri Compromise box; they got ten more years to lash their chattels; the federal government and all the free states committed themselves to assist the said lashing, under the Fugitive Slave Act; and the monster slave state of Texas was created in its present bloated bounds, an acquisition I for one could have done without.

In short, an approving reference to the Compromise Of 1850 is an excellent illustration of the Madness Of The Center, a topic which is becoming a downright hobbyhorse for me.

I think my disembodied radio expert was mostly impressed by the ingenuity of the manoeuvre; a matter of the means justifying the end. For more ponderous thumbsuckers, the case for the Compromise is that it was good for ‘the country’ — which is to say, that it set ‘the country’ on course to become the monstrosity it now is. Had the Compromise not occurred, some other monstrosity would have resulted. Would it have been a worse monstrosity, or a better one?

The Subjunctivists are sure they know; and I’m sure they don’t. What I do know is that the Viral Center is in love with the monstrosity we have, and is happy to speak well of whatever brought this particular rough beast to birthing.

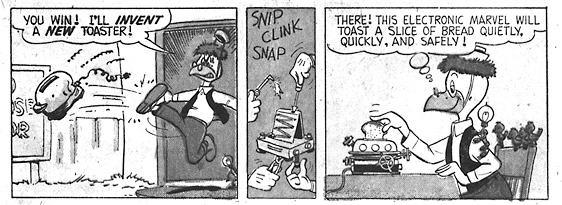

Fugitive Slave Act and all. Hey, you can’t make an omelette without beating a few slaves.